NEW YORK —

During his decades as an artist, British painter Leon Kossoff (1926-2019)

produced 510 known oil paintings. This can be said because they have all been

tracked down and published in a catalogue raisonné just out from

Modern Art Press (London).

اضافة اعلان

A catalogue

raisonné is a herculean effort of research, detective work, devotion and

perception. This one, assembled over eight years by a small team led by Andrea

Rose, an art historian and specialist in British painting, conveys the usual

breathtaking accumulation of information: images of each painting, its

exhibition history and bibliography, and a list of its successive owners

(called a provenance).

An added benefit

is the liveliness of Rose’s annotations of the paintings, which are peppered

with striking observations from sundry art historians, curators, critics,

artists, the artist himself and others. One of Kossoff’s two small paintings

based on Titian’s horrific “Apollo Flaying Marsyas,” for example, comes with an

insightful appreciation by David Bowie, who once owned it.

(Photo: NYTimes)

(Photo: NYTimes)

The publication of

a catalogue raisonné is a momentous event, and Kossoff’s is being celebrated by

the exhibition “Leon Kossoff: A Life in Painting,” a title shared by three

small, carefully thought-out surveys at the artist’s primary galleries:

Mitchell-Innes & Nash in New York,

Annely Juda Fine Art in London and LA

Louver in Los Angeles. A collective catalog reproduces the works in all three

of them, which is admirable. It also calls the combined shows “the largest most

comprehensive exhibition” of Kossoff’s paintings ever staged in a commercial

gallery, which seems an empty boast.

By now, Kossoff is

among the most accomplished painters of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

He has been unfairly overshadowed by fellow Brits like Francis Bacon and Lucian

Freud, thanks in part to their colorful personal lives. But this may pass.

Kossoff’s

greatness lies in the extreme way he pits the two basic realities of painting —

the actual paint surface and the image depicted — against each another. First

there is the startlingly heavy, even off-putting, impasto of his oil paint,

which sometimes seems more ladled on than conventionally applied with a brush

(even a big one), and which gives his surfaces an almost topographical

dimension. Then there is the reality of his images, initially swamped in paint,

that ultimately battles its way to legibility through a process that

thrillingly slows and extends the act of looking.

The painter’s

subjects fall into two main groups. There are self-portraits as well as

portraits of friends and family and paintings of nude models — all made during

long sessions in his studio. Then there is everything outside, namely London

and its pulsing life. This he captured in paintings of construction sites,

pedestrians passing well-known buildings or entering tube stations, and trains

racing along tracks. These began as numerous drawings made on location, from

which he painted in the studio.

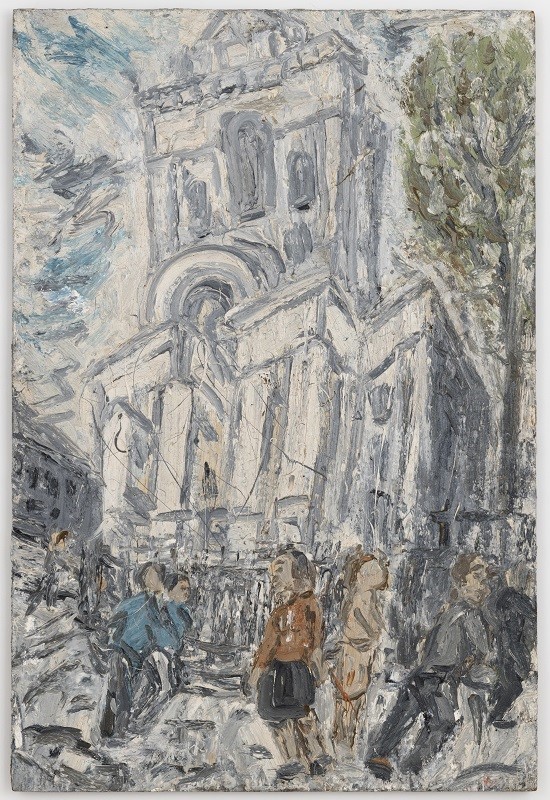

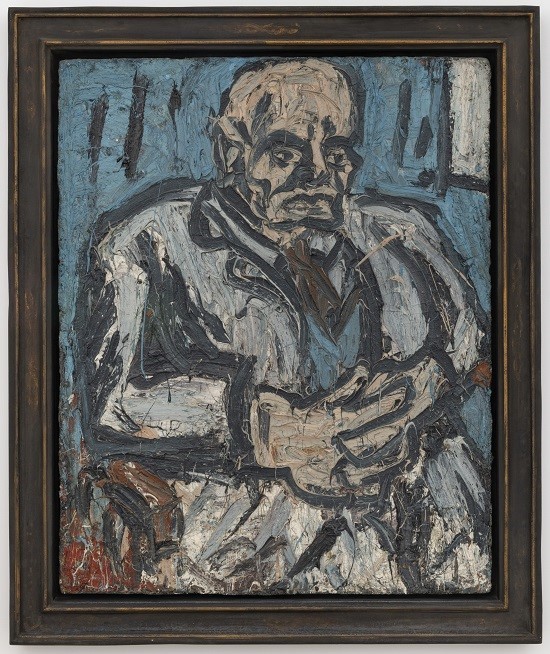

The 13 paintings

at Mitchell-Innes & Nash span three decades and most of his subjects. They

begin with the large “Seated Nude No. 1” (1963) — a Rubenesque woman sinking

into a dark armchair — full of early signals of his vision. Among other

standouts is a 1992 rendering of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s English baroque

masterpiece, Christ Church, Spitalfields in the East End, towering protectively

above the people hurrying past on the sidewalk; a powerful seated portrait of

his father; a roiling demolition scene; and two passing trains viewed from

above, through trees.

(Photo: NYTimes)

(Photo: NYTimes)

The great thing

about Kossoff’s paintings is the ultimate accuracy of their portrayals, in the

psychic and physical sense. All his subjects come across as complex presences,

living parts of the living world — whether human, architectural or natural —

animated by his thick, quietly vibrating surfaces.

It is telling that the

only still life in the entire catalogue raisonné is from the early 1950s, when

Kossoff was just getting started. Even his paintings based on the old masters

are usually multifigure compositions to which he adds his own special sense of

tumult. This is exemplified in this superb show by the lunging bodies and

brushwork in his copy of a Poussin. He had little interest in stillness.

Read more Culture and Arts