The

Azraq Wetlands Reserve is one of Jordan’s lesser-known

national parks, but it is definitely worth a visit. We went independently by

car, but the reserve is managed by the

Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN), so there are a variety of organized tours available through Wild

Jordan, an eco-tourism company which operates under the auspices of the RSCN.

اضافة اعلان

After paying for the longer tour at the reserve, which I

think is worth the additional fee if you actually want to see many birds, we

drove north up Route 40 about 20 minutes and walked about one kilometer from

our parking spot to Qasr Al-Usaykhim, a ruined fortress with sweeping views of

the barren basalt desert on the border of

Zarqa and Mafraq governorates.

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

This week’s destination is more hidden gem than hike, and it

definitely helps to have a car. Azraq is about a two-hour drive from

Amman, and

it might be possible to get there by taking a bus to Zarqa and then another one

to Azraq, but it would be an involved logistical challenge.

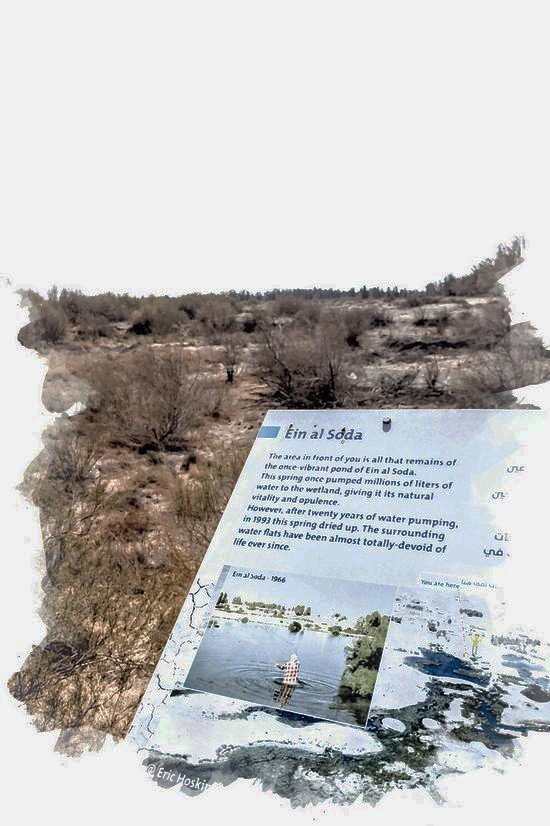

The wetland reserve is as much an educational experience in

devastating ecological tragedy as it is a natural destination, and as beautiful

as the marsh is in the small area where it has been artificially preserved by

RSCN efforts to pump water back into the area, it is sad to realize what an incredibly

large, lush, and biodiverse area it used to be before the springs completely

dried out due to unsustainable human activity.

Jordan’s

Azraq Basin features large underground water

aquifers, and the area became a wetland around 250,000 BC. Since ancient times,

it served as a stop-over for migratory birds from Africa, Europe, and Asia, as

well as a waypoint for migrating humans and land mammals. An extension of

Africa’s ecosystems, Azraq and its vast wetlands used to be home to species

including the

Syrian wild ass, wild camel, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, Asian

elephant, gazelle, aurochs, Asiatic cheetah, Syrian

ostrich, Asiatic

lion, and

Arabian oryx. All these animals except for the gazelle are now extinct in

Jordan.

As recently in the 1960s, naturalists would record close to

350,000 birds stopping at the wetlands along their migration routes. In the

wake of decades of unsustainable amounts of water being pumped out of the

aquifers for urban and agricultural purposes, particularly to serve the booming

populations of Amman and Zarqa, the natural

springs completely dried up in

1992. In the mid-90s, the RSCN started pumping enough water back into the area

to restore a mere 10 percent of the wetlands, and some of the birds returned —

1,200 were recorded in the year 2000.

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

The employees of the RSCN and the

Azraq Reserve are

passionate about conservation and the preservation of Jordan’s natural species

and habitats, and our tour of the 3km “Water Buffalo Trail” with local guide

Majd Qadi was well worth the price — JD6 for Jordanians, JD9 for residents and

students, and JD12 for foreigners.

Qadi, who is the reserve’s head eco-education officer, has

personally observed over 180 species of birds there. He pointed out different

birdsongs, cluing us in to the presence of graceful prinias and white-cheeked

bulbuls, and identified a nest in the reeds as the home of a reed warbler.

He told us how the reserve had reintroduced water buffaloes,

which were originally brought by the region’s first

Chechen migrants but

eventually died out due to the water issues. The reserve now maintains of herd

of 17, which we did not see, because they eat down some of the vegetation and

create natural trails through the marsh.

Qadi also told us, after we noticed some movement in the

water, that in addition to frogs, snakes, lizards, and crabs, the Azraq

wetlands are home to the aphanus sirhani, or Azraq toothcarp, a species of

killifish endemic to Jordan and not found anywhere else in the world. There is

a photo there from 1966 of a local man fishing with a casting-net, standing

waist-deep in the water in an area that is now completely dry and barren.

It was breathtaking, and it was also mind-boggling to see some of the bird species I know from my home on the shore of a salty estuary on the US east coast in a very similar wetland habitat in the middle of the Jordanian desert.

The highlight of the experience was our quiet entrance into

the second bird hide on the walk, a rustic hut built over one of the ponds with

short but panoramic open windows to view the marsh. Eagerly scanning with our

cameras and the binoculars provided to us at the reserve, we saw hundreds of

birds, including great white egrets, gray herons, black-winged stilts,

waterhens, terns, and a variety of ducks, including white shovelers, pintails,

little grebes, coots, and teals. We even saw a bird of prey, a marsh harrier,

calmly circling from above before settling into the reeds.

It was breathtaking, and it was also mind-boggling to see

some of the bird species I know from my home on the shore of a salty estuary on

the

US east coast in a very similar wetland habitat in the middle of the

Jordanian desert.

We were lucky to see so many species, as we learned upon our

arrival at about 11am that we were a bit early in the season and a bit late in

the day: Azraq’s peak bird-watching seasons are in the spring and autumn,

peaking in late April and mid-October, respectively, and birds are more active

early in the morning, so it is recommended to arrive at the reserve as close to

its 9am opening as possible.

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

(Photo: Zane Wolfang/Jordan News)

After leaving the reserve, we traveled north into the desert

to find Qasr Al-Usaykhim. It sits atop the tallest hill in the area, with a

commanding view of the tawny desert and fields of black basalt stones stretching

into the distance in every direction, and is built from basalt, with much of

the walls, two arches and a lower stone wall encircling the elevated site still

intact. There is no information or amenities at the site, but the

Wild Jordan

brochure explains that the fortress marked the easternmost point of the ancient

Roman empire.

The site is easy to get to and free to enter, and the

landscape is stunning, stony and barren, in stark contrast to the wetlands only

23 kilometers to the south. Seeing that landscape made the wetlands seem even

more special, and the story of their destruction at the hands of humanity all

the more devastating.

There are two other “desert castles” in the area, as well as

the Shaumari wildlife reserve and Azraq castle in the main town of Azraq, so

there are some choices to mix and match destinations and come up with your own

unique adventure.

Wild Jordan also offers a guided bicycle tour loop of the

area. Bring your own water, definitely bring your camera to the wetland reserve

if you have one, and be sure to visit the small educational exhibit inside the

reserve visitor center to learn about the ecological history of the area and

the conservation efforts of the RSCN.

Read more Where to Go