Chef Tanya Holland chronicles the journey of ‘California Soul’

New York Times

last updated: Dec 01,2022

At 6am on a recent Tuesday, chef Tanya

Holland sat alert in the green room of “Good Morning America” just off Times

Square in New York, asking her small team if they needed anything. With dozens

of television appearances under her belt, Holland did not seem nervous, but

instead used this quiet moment to rehearse her brief cooking segment.اضافة اعلان

“I’ve done this many times,” she said while getting a touch-up from her makeup artist. Her mood was meditative, despite the hundred moving pieces in the studio.

It was not unlike the morning routine she kept at her restaurant, Brown Sugar Kitchen, nearly 4,800km away in Oakland, California. As the chef and owner of the US soul-food restaurant, which was open 2008 to 2021, Holland began most days at 5:30am, heating oil in anticipation of orders of fried chicken, boiling water for poached eggs, signing off on orders of fresh produce, and baking pecan-topped sticky buns to a golden brown as customers began to queue outside.

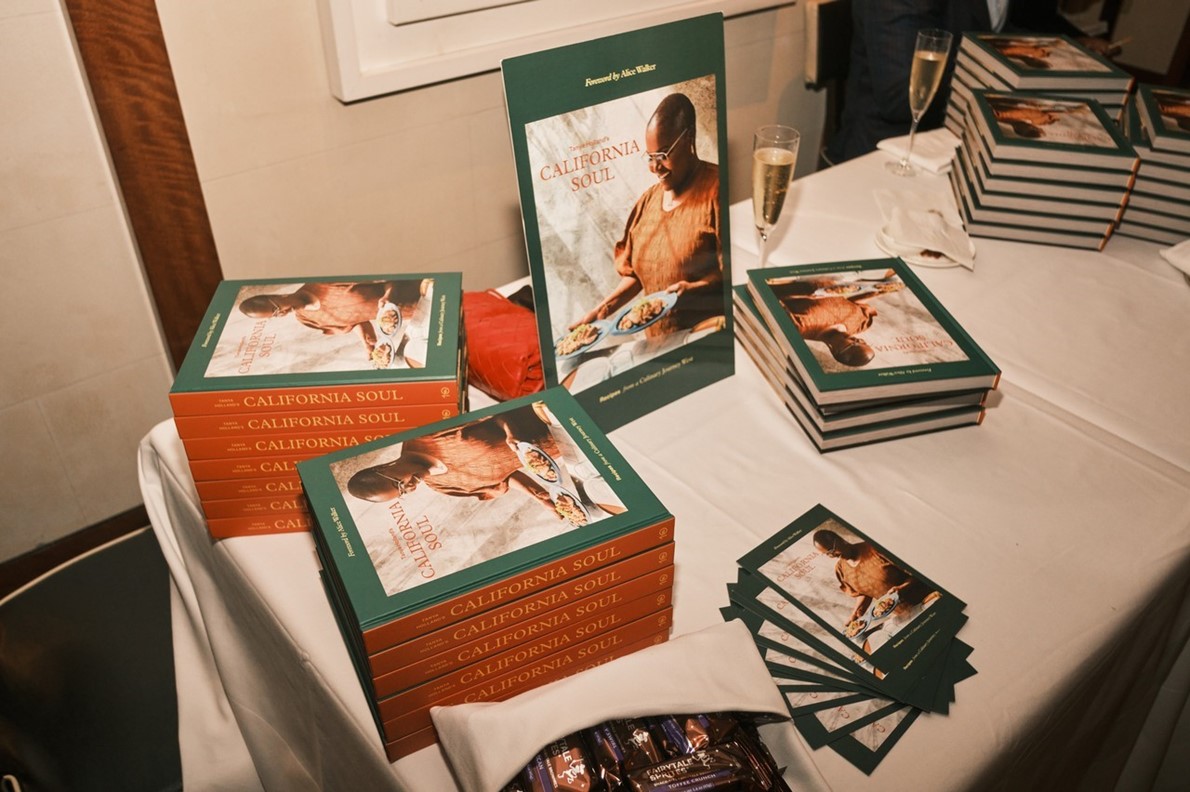

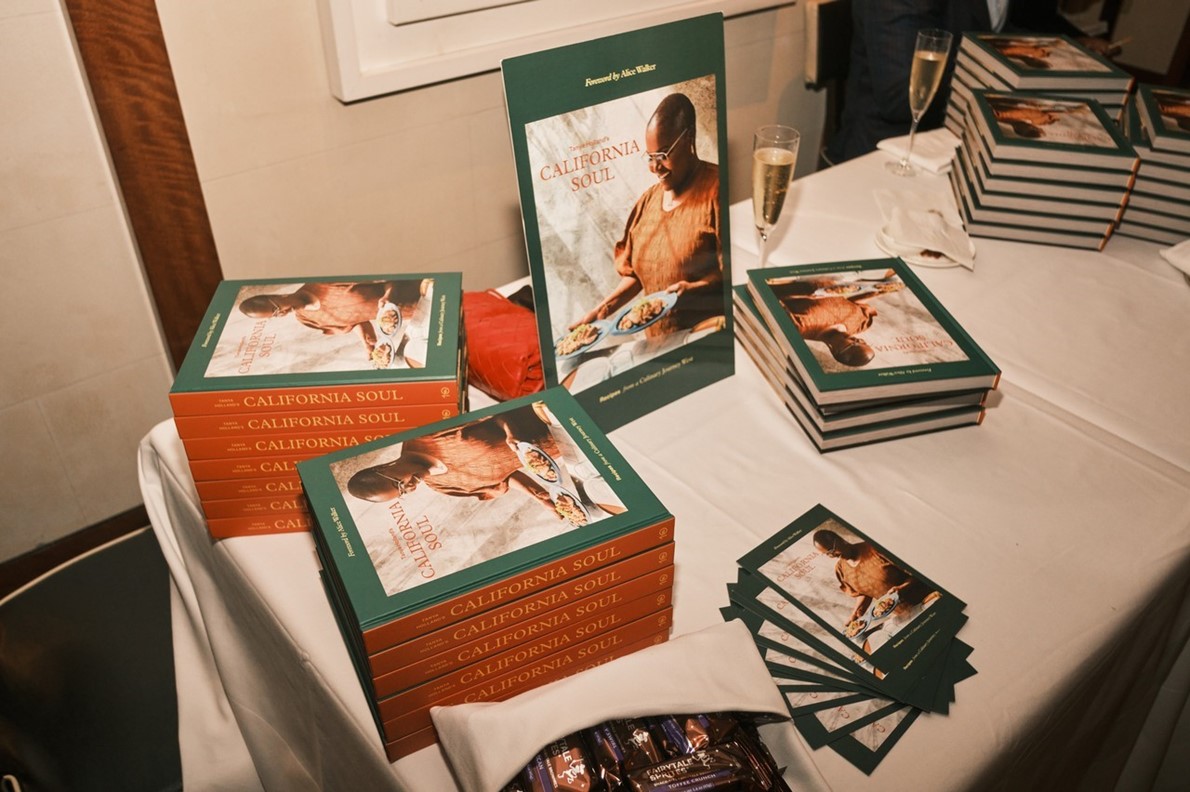

Copies of Tanya Holland’s latest book, ‘Tanya Holland’s California Soul: Recipes From a Culinary Journey West’, at a book signing in New York, October 25, 2022.

In Oakland, Holland built a reputation for cooking that blended Southern cuisine with California influences and French technique, becoming a pillar of the Bay Area culinary community and winning three Michelin Bib Gourmand awards along the way. She even hosted her own television show, “Tanya’s Kitchen Table”, on the OWN network. Her latest book, “Tanya Holland’s California Soul: Recipes From a Culinary Journey West”, tells the stories of California’s Black food history, a melting pot of influences from all over the country.

But on this day in New York City, Holland, 57, beamed under the stage lights as she talked on camera about the apple-cider-braised pork chops and chunky cooked apples that she was cooking on the set. The recipe was inspired in part by her paternal grandmother.

“I spent summers with her in Virginia, and apples were like a condiment at the breakfast table,” she said as thick slices of Granny Smiths caramelized in a cast-iron pan in front of her. “It’s like an ode to her.”

This dish is one of the many in “California Soul” that celebrates the Black farmers, cooks, and artisans who changed that state’s cuisine.

Written with Maria C. Hunt and Dr Kelley Fanto Deetz, it also chronicles the westward movement of Black people during the Great Migration, specifically the second wave, from 1940 to 1970, when African Americans from Louisiana and Texas moved to cities like Oakland and Los Angeles in search of employment and the promise of full citizenship.

“The Great Migration is the most acute and dramatic demographic transformation in 20th-century United States history,” said Karida Brown, a professor of sociology at Emory University and the author of “Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia”.

Before the migration, 90 percent of African Americans lived in the South, Brown said. When 6 million of them moved to points in northern, midwestern, and western states, the shift created a need for community in those places. Restaurants became an important vehicle for preserving Black culture, including cooking that evoked a sense of home.

“People packed up shoes, clothes but also hopes, dreams, religious practices, food, and sayings,” Brown said.

Black cooks created a distinctive California variation on Black foodways, in which traditional Southern recipes met local produce. Dungeness crab became a replacement for blue crab. Cooks used rice grown in the Sacramento Valley (a legacy of the Chinese railroad workers and gold miners who had moved there in the 19th century) to re-create dishes from Louisiana like jambalaya and dirty rice. Santa Maria-style barbecue blended with Texan smokehouse traditions.

As Holland put it, “Soul food is wherever African Americans live, not just in the South. It’s migration cuisine, really.”

The abundance and variety of fresh produce in California has also led many immigrant groups to create different iterations of their cuisines, said Brandon Jew, the executive chef and owner of Mister Jiu’s in San Francisco. That is the essence of the California ethos and of his own cooking, he said. “It’s really the love of ingredients, and translating them through different regions.”

The recipes in “California Soul” reflect Holland’s childhood in the Northeast, her time as a culinary student in France, and the years she has lived in California. Cornmeal-based hoe cakes are topped with dollops of caviar and crème fraîche, while barbecued oysters (a Northern California specialty) are broiled with a bacon-vinegar mignonette. Her take on gumbo is brightened with fresh green herbs and kale. The dish she calls “dirty potato salad with all the peppers and onions” is based on Southern-style dirty rice, and the flavor of buttery yeasted rolls is buttressed by whipped sweet potatoes.

Although this is her third book, it feels the most representative of her cooking, Holland said. “This is the food I would cook if no one was looking.”

Chef Tanya Holland at her restaurant Brown Sugar Kitchen in Oakland, California, on October 22, 2015.

Born in Connecticut and raised in Rochester, New York, by parents from Louisiana and Virginia, Holland trained in Burgundy at the prestigious École de Cuisine La Varenne after graduating from the University of Virginia. She worked in traditional French-style kitchens in the United States, but said she was routinely denied the opportunity to learn new skills or move up the ranks.

“I was feeling so limited, and I’ve always been ambitious, even from a young age,” she said.

It became clear that she would have to create her own opportunities. Holland took a course on “the business of food” at New York University in 1996 and met the groundbreaking chef Patrick Clark when he came to speak to the class. They kept in touch, and several years later, she asked him for advice.

“I went to him and told him I wanted to own my own restaurant,” she recalled. “He said, ‘Tanya, leave New York.’”

In 2001, Holland took his advice and moved to the Bay Area. Seven years later, after working in catering for many years, she opened Brown Sugar Kitchen, a casual, 50-seat quasi-diner serving soul food in a cinnamon-colored building on a nondescript stretch of Mandela Parkway in West Oakland.

“It’s funny; the first restaurant I worked at in California was the one that I owned,” she said.

She bought dairy, breads, and meats locally, finding a community with other business owners in Oakland who were supportive rather than competitive. “There were more women chefs/owners of restaurants in California,” she said, “and professionally, people were more collegial, so there was always someone I could turn to if I had questions.”

Brown Sugar Kitchen quickly drew acclaim from the local and national press for its shrimp and grits, pecan sticky buns, and fried chicken and waffles. Critic Jonathan Gold wrote in 2009 that the first time he tasted Holland’s yeasted cornmeal waffles, “it was almost as if I had never tasted a waffle at all. Because Brown Sugar’s waffles, so violently risen that it is as if the batter had tried to lift itself from the devilishly hot waffle iron toward the firmament, are so light and so crisp that they are almost a different species.”

The success of her restaurant allowed Holland to become an ambassador for Oakland and California at large.

“It felt like an old-school Black soul-food restaurant, but also it had a new and modern, nostalgic quality to it,” said Keba Konte, the owner of Red Bay Coffee, a roastery and small coffee shop chain based in Oakland, who is featured in “California Soul”. “It was soul food in the California way, but without veering too far from the original.”

And as Brown Sugar Kitchen won more acclaim, it encouraged other business owners. “When people turn up the pace, it makes everyone stand up a little taller,” Konte said. “She’s made me step up my game. It just elevates everyone.”

The City of Oakland declared June 5, 2012, Tanya Holland Day for her “significant role in creating community and establishing Oakland as a culinary center”.

Holland went on to own four more restaurants in the Bay Area and last December closed the last of them, Brown Sugar Kitchen’s second location in downtown Oakland. Now, not having to be in a restaurant every day, she is traveling, appearing on television shows, and taking on various new projects.

She is also working with the James Beard Foundation, as a board member and chair of the awards committee, to make its awards program more inclusive and equitable. “I’m going to impact the board the way I always do: by being at the table and in the room,” she said.

Jew said she is still a role model for future chefs, even if she is no longer in a kitchen. “She has opened a lot of doors,” he said, especially for chefs of color. “She’s really an example of how you can build a career and sustain it even after having a restaurant. That’s longevity.”

As for opening another restaurant, Holland said that chapter of her life is complete for now.

“I think I’m done with that, although I’ll always love hospitality,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to create a legacy so I can reach women in other communities and continue to share my knowledge.”

Read more Good Food

Jordan News

“I’ve done this many times,” she said while getting a touch-up from her makeup artist. Her mood was meditative, despite the hundred moving pieces in the studio.

It was not unlike the morning routine she kept at her restaurant, Brown Sugar Kitchen, nearly 4,800km away in Oakland, California. As the chef and owner of the US soul-food restaurant, which was open 2008 to 2021, Holland began most days at 5:30am, heating oil in anticipation of orders of fried chicken, boiling water for poached eggs, signing off on orders of fresh produce, and baking pecan-topped sticky buns to a golden brown as customers began to queue outside.

Copies of Tanya Holland’s latest book, ‘Tanya Holland’s California Soul: Recipes From a Culinary Journey West’, at a book signing in New York, October 25, 2022.

In Oakland, Holland built a reputation for cooking that blended Southern cuisine with California influences and French technique, becoming a pillar of the Bay Area culinary community and winning three Michelin Bib Gourmand awards along the way. She even hosted her own television show, “Tanya’s Kitchen Table”, on the OWN network. Her latest book, “Tanya Holland’s California Soul: Recipes From a Culinary Journey West”, tells the stories of California’s Black food history, a melting pot of influences from all over the country.

But on this day in New York City, Holland, 57, beamed under the stage lights as she talked on camera about the apple-cider-braised pork chops and chunky cooked apples that she was cooking on the set. The recipe was inspired in part by her paternal grandmother.

“I spent summers with her in Virginia, and apples were like a condiment at the breakfast table,” she said as thick slices of Granny Smiths caramelized in a cast-iron pan in front of her. “It’s like an ode to her.”

This dish is one of the many in “California Soul” that celebrates the Black farmers, cooks, and artisans who changed that state’s cuisine.

Written with Maria C. Hunt and Dr Kelley Fanto Deetz, it also chronicles the westward movement of Black people during the Great Migration, specifically the second wave, from 1940 to 1970, when African Americans from Louisiana and Texas moved to cities like Oakland and Los Angeles in search of employment and the promise of full citizenship.

“The Great Migration is the most acute and dramatic demographic transformation in 20th-century United States history,” said Karida Brown, a professor of sociology at Emory University and the author of “Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia”.

Before the migration, 90 percent of African Americans lived in the South, Brown said. When 6 million of them moved to points in northern, midwestern, and western states, the shift created a need for community in those places. Restaurants became an important vehicle for preserving Black culture, including cooking that evoked a sense of home.

“People packed up shoes, clothes but also hopes, dreams, religious practices, food, and sayings,” Brown said.

Black cooks created a distinctive California variation on Black foodways, in which traditional Southern recipes met local produce. Dungeness crab became a replacement for blue crab. Cooks used rice grown in the Sacramento Valley (a legacy of the Chinese railroad workers and gold miners who had moved there in the 19th century) to re-create dishes from Louisiana like jambalaya and dirty rice. Santa Maria-style barbecue blended with Texan smokehouse traditions.

As Holland put it, “Soul food is wherever African Americans live, not just in the South. It’s migration cuisine, really.”

The abundance and variety of fresh produce in California has also led many immigrant groups to create different iterations of their cuisines, said Brandon Jew, the executive chef and owner of Mister Jiu’s in San Francisco. That is the essence of the California ethos and of his own cooking, he said. “It’s really the love of ingredients, and translating them through different regions.”

The recipes in “California Soul” reflect Holland’s childhood in the Northeast, her time as a culinary student in France, and the years she has lived in California. Cornmeal-based hoe cakes are topped with dollops of caviar and crème fraîche, while barbecued oysters (a Northern California specialty) are broiled with a bacon-vinegar mignonette. Her take on gumbo is brightened with fresh green herbs and kale. The dish she calls “dirty potato salad with all the peppers and onions” is based on Southern-style dirty rice, and the flavor of buttery yeasted rolls is buttressed by whipped sweet potatoes.

Although this is her third book, it feels the most representative of her cooking, Holland said. “This is the food I would cook if no one was looking.”

Chef Tanya Holland at her restaurant Brown Sugar Kitchen in Oakland, California, on October 22, 2015.

Born in Connecticut and raised in Rochester, New York, by parents from Louisiana and Virginia, Holland trained in Burgundy at the prestigious École de Cuisine La Varenne after graduating from the University of Virginia. She worked in traditional French-style kitchens in the United States, but said she was routinely denied the opportunity to learn new skills or move up the ranks.

“I was feeling so limited, and I’ve always been ambitious, even from a young age,” she said.

It became clear that she would have to create her own opportunities. Holland took a course on “the business of food” at New York University in 1996 and met the groundbreaking chef Patrick Clark when he came to speak to the class. They kept in touch, and several years later, she asked him for advice.

“I went to him and told him I wanted to own my own restaurant,” she recalled. “He said, ‘Tanya, leave New York.’”

In 2001, Holland took his advice and moved to the Bay Area. Seven years later, after working in catering for many years, she opened Brown Sugar Kitchen, a casual, 50-seat quasi-diner serving soul food in a cinnamon-colored building on a nondescript stretch of Mandela Parkway in West Oakland.

“It’s funny; the first restaurant I worked at in California was the one that I owned,” she said.

She bought dairy, breads, and meats locally, finding a community with other business owners in Oakland who were supportive rather than competitive. “There were more women chefs/owners of restaurants in California,” she said, “and professionally, people were more collegial, so there was always someone I could turn to if I had questions.”

Brown Sugar Kitchen quickly drew acclaim from the local and national press for its shrimp and grits, pecan sticky buns, and fried chicken and waffles. Critic Jonathan Gold wrote in 2009 that the first time he tasted Holland’s yeasted cornmeal waffles, “it was almost as if I had never tasted a waffle at all. Because Brown Sugar’s waffles, so violently risen that it is as if the batter had tried to lift itself from the devilishly hot waffle iron toward the firmament, are so light and so crisp that they are almost a different species.”

The success of her restaurant allowed Holland to become an ambassador for Oakland and California at large.

“It felt like an old-school Black soul-food restaurant, but also it had a new and modern, nostalgic quality to it,” said Keba Konte, the owner of Red Bay Coffee, a roastery and small coffee shop chain based in Oakland, who is featured in “California Soul”. “It was soul food in the California way, but without veering too far from the original.”

And as Brown Sugar Kitchen won more acclaim, it encouraged other business owners. “When people turn up the pace, it makes everyone stand up a little taller,” Konte said. “She’s made me step up my game. It just elevates everyone.”

The City of Oakland declared June 5, 2012, Tanya Holland Day for her “significant role in creating community and establishing Oakland as a culinary center”.

Holland went on to own four more restaurants in the Bay Area and last December closed the last of them, Brown Sugar Kitchen’s second location in downtown Oakland. Now, not having to be in a restaurant every day, she is traveling, appearing on television shows, and taking on various new projects.

She is also working with the James Beard Foundation, as a board member and chair of the awards committee, to make its awards program more inclusive and equitable. “I’m going to impact the board the way I always do: by being at the table and in the room,” she said.

Jew said she is still a role model for future chefs, even if she is no longer in a kitchen. “She has opened a lot of doors,” he said, especially for chefs of color. “She’s really an example of how you can build a career and sustain it even after having a restaurant. That’s longevity.”

As for opening another restaurant, Holland said that chapter of her life is complete for now.

“I think I’m done with that, although I’ll always love hospitality,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to create a legacy so I can reach women in other communities and continue to share my knowledge.”

Read more Good Food

Jordan News