This essay was published first by New Lines Magazine on January 1, 2024.اضافة اعلان

As

has become a tradition in our magazine, we wanted to usher in the new year with

a list of the best books our editors read in 2023. These are not necessarily

books published that year — the idea is to pick reads that were especially

meaningful or delightful.

The Skull: A Tyrolean Folktaleby Jon Klassen

The Skull: A Tyrolean Folktaleby Jon Klassen

Jos Betts, Senior Editor

A

girl runs away from something unnamed through the forest and is taken in by a

disembodied skull, whose castle contains another nocturnal pursuer that the

girl will have to face. The first time I read this with my daughter I was

surprised by its simplicity, but, like the best folk tales, it has lingered,

unfolding the idea that having someone to save can tame your fear.

Hamnetby Maggie O’Farrel

Hamnetby Maggie O’Farrel

Erin Clare Brown, North Africa

Editor

This

year, I read — or rather listened to — dozens of books by women and about

women. It wasn’t out of some feminist impulse, but I spent half of the year on

my own with my young daughter, and stories of the internal lives of women felt

particularly close to me. Of the many I read, Maggie O’Farrell’s “Hamnet” was

an easy favorite.

Set

in 1596, during one of the many waves of the plague in England, the book

explores the life of a mysterious, warm, and powerful woman named Agnes, along

with her three children and her husband — a glovemaker’s son and Latin tutor

who goes on to perform in and write plays. (He is the only character whose

first name is never said or written in the novel, but we all know it is William

— William Shakespeare.) When their young son dies of the plague, aged 11, it

rends the family apart, and the novel is a gorgeous portrait of grief and

longing and the chasms that open in marriages and love when loss arrives.

Rules: A Short History of What We Live By

Rules: A Short History of What We Live By

by Lorraine Daston

Rasha Elass, Editorial Director

We

all grow up with rules and we internalize most of them until they become part

of our unconscious. Even animals have rules, especially those that live within

a tight social order, like wolves and primates. From an early age, they learn

not to mess with the alphas and how to engage with their equals in reciprocal

social behavior; rules, and “culture” that become an animal’s nature.

This

may not be too different from us humans. We find ourselves raised in a society

where the rules were written, synthesized, codified, and enforced for

generations before we were even born. But unlike other species in the animal

kingdom, not only are we fully capable of questioning the rules, we can

deconstruct and trace them back to their origins, which, as we know, can be an

unsavory place.

This

is why I enjoyed reading Lorraine Daston’s book, “Rules: A Short History of What

We Live By,” which takes a deep dive into the algorithms, laws, and models that

we’ve constructed for ourselves over millennia, and forgotten how we did so. In

the process, this book illuminates the constrictions that we’ve invented and

put in place for ourselves and, by understanding those, the potential for

freeing humanity from its limited mind.

The Executioner’s Songby Norman

Mailer

The Executioner’s Songby Norman

Mailer

Tam Hussein, Associate Editor

You

either love Norman Mailer’s writing or you hate it. When he wrote “The Fight,”

about Muhammad Ali and George Foreman’s “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa in

1974, it was marred by his presence in the book. Writing about himself in the

third person felt pompous. But when he writes like he does in “The

Executioner’s Song,” you love him. The book is a voluminous tome; a hybrid of

sorts — part crime novel and part journalism — which, despite its size, is

always a page-turner. The story is a dissection of the twisted Gary Gilmore, an

unsympathetic ex-con, who commits senseless murders. He only redeems himself by

finding a sort of peace in wanting to be executed and coming to terms with his

extinction — something few of us do. It is a profound rumination in this

regard.

But

more than that, “The Executioner’s Song” is an argument for really good

investigative journalism. Mailer interviews countless family members and

associates to paint a deep picture of Gilmore. Sometimes you indeed feel it

could do with an edit, but the picture is so vivid you forgive it.

As

an investigator, you can’t but admire the amount of legwork that Mailer had to

put in. Remember those were the days when open-source investigations (OSINT)

were not even a thing. When you read the book, it is a reminder that profound

stories like these come about from human contact, rummaging through archives,

and visiting the scene, and not from using open-source tools in the bedroom.

Good journalism depends on engaging with the wider world. Mailer brings to life

society, court records, lawyers, girlfriends, employers, and others so well

that he teaches you something about the dark and indeed the light heart of

Americana.

No wonder the book won the Pulitzer.

Journalists, investigators, and students should revisit this book.

Minor Detail

Minor Detail

by Adania Shibli

Christin El-Kholy, Multimedia

Producer

One

of the most impactful reads for me this year has to be Adania Shibli’s 2020

novel “Minor Detail,” a thought-provoking and evocative work that weaves

together two seemingly disparate narratives separated by decades. The novel is

divided into two parts, with the first part set in 1949, just after the Nakba,

and the second in the contemporary era. Shibli masterfully captures the

psychological and emotional dimensions of her characters, delving into the

complexities of history and human experience. She invites readers to reflect on

the nature of memory, the persistence of trauma, and how historical injustices

continue to shape the present — and there is no better time to do that.

I

found myself challenged at every corner by this short but haunting book that

resonated long after the final page. Perhaps this is why “Minor Detail” had

been on the radar of reviewers and literary-award bodies even before it made

headlines just a few months ago. Shibli, a Palestinian, had been announced as

the winner of Litprom’s 2023 LiBeraturpreis literature award, but after the

Oct. 7 attacks, Litprom, which is funded in part by the German government,

decided to cancel the award ceremony.

Met

with backlash from editors, writers, and supporters from all over the world —

which culminated in a widely circulated open letter of support for Shibli —

this move has not only resulted in the unintended newfound success of the book

but has also opened up the conversation about the role that editors,

translators, publishers, awards judges, and other cultural guardians play in

such times (as discussed in a recent episode of The Lede).

Tell Me I’m Worthlessby Alison Rumfitt

Tell Me I’m Worthlessby Alison Rumfitt

Joshua Martin, Multimedia Producer

I’d

thought the haunted house story was as dead as the ghosts themselves by this

point. Things go bump, ghost goes boo, we’ve seen it all before. But in an

impressive act of literary necromancy, Alison Rumfitt somehow managed to

breathe new life into an old staple of the horror genre.

“Tell

Me I’m Worthless” keeps the house but dispenses with the worn-out poltergeists.

It’s not ghosts doing the haunting, but fascism (and also sometimes Morrissey).

It’s a conceit that might run the risk of becoming didactic, but Rumfitt never

loses focus on telling a good story or runs out of interesting things to say.

It’s a terrifying, nauseating, and insightful look into the dark heart of

modern Britain, and it made me feel unclean.

Writers and Missionariesby Adam Shatz

Writers and Missionariesby Adam Shatz

Danny Postel, Politics Editor

The

title of this book comes from something the Trinidadian writer V.S. Naipaul

once said to its author, Adam Shatz, during an interview: “You have to make a

choice — are you a writer, or are you a missionary?” The remark resonated with

Shatz, who later reflected: “Naipaul was evoking the tension between the

writer, who describes things as he or she sees them, and the missionary or the

advocate, who describes things as he or she wishes they might be under the

influence of a party, movement or cause.”

Over

time, Shatz came to see his early writings as the work of a missionary —

rereading them, he found “the tone jarring, the confidence unearned, the lack

of humility suspect” — and aspired to be a writer. As an admirer of Shatz’s

discerning, intensely absorbing essays for over two decades now, I was thrilled

to see some of his greatest hits assembled in book form here. Among the figures

he explores in this volume are the Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said,

the African-American novelist Richard Wright, the Algerian novelist Kamel

Daoud, the French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann (director of the Holocaust

documentary “Shoah”), the French novelist and controversialist Michel

Houellebecq, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the Egyptian essayist

Arwa Salih. His examination of the metamorphosis of the Lebanese thinker Fouad

Ajami from Arab nationalist to neoconservative ideologue is worth the price of

admission alone. “His once-luminous writing,” Shatz comments, had devolved into

“a blend of Naipaulean clichés about Muslim pathologies and Churchillian

rhetoric about the burdens of empire.”

Like

Henry Kissinger, Shatz notes, Ajami possessed “a suave television demeanor, a

gravitas-lending accent, an instinctive solicitude for the imperatives of power

and a cool disdain for the weak.” The critique is stinging but the essay is far

from a hatchet job: Shatz probes the contours of Ajami’s intellectual and

political biography and provides a close, quite sympathetic reading of his

early work.

This

book is a master class in the international journalism of ideas. What makes

Shatz such a compelling critic is his refusal, as a former colleague of mine

once put it, to edit out the contradictions.

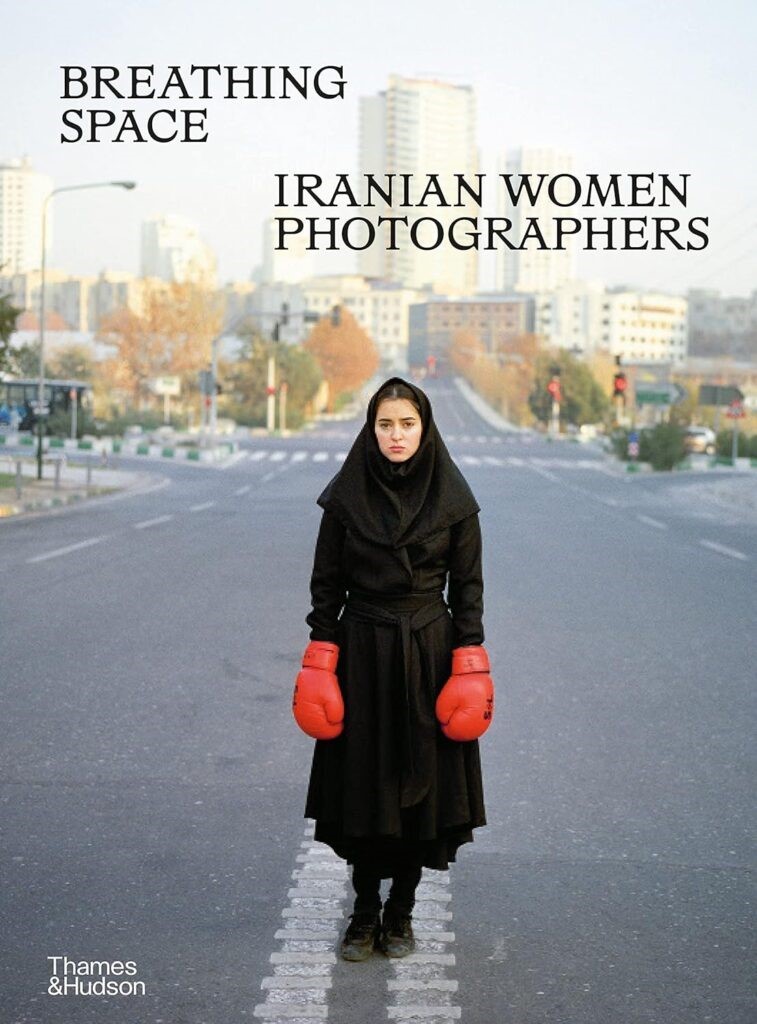

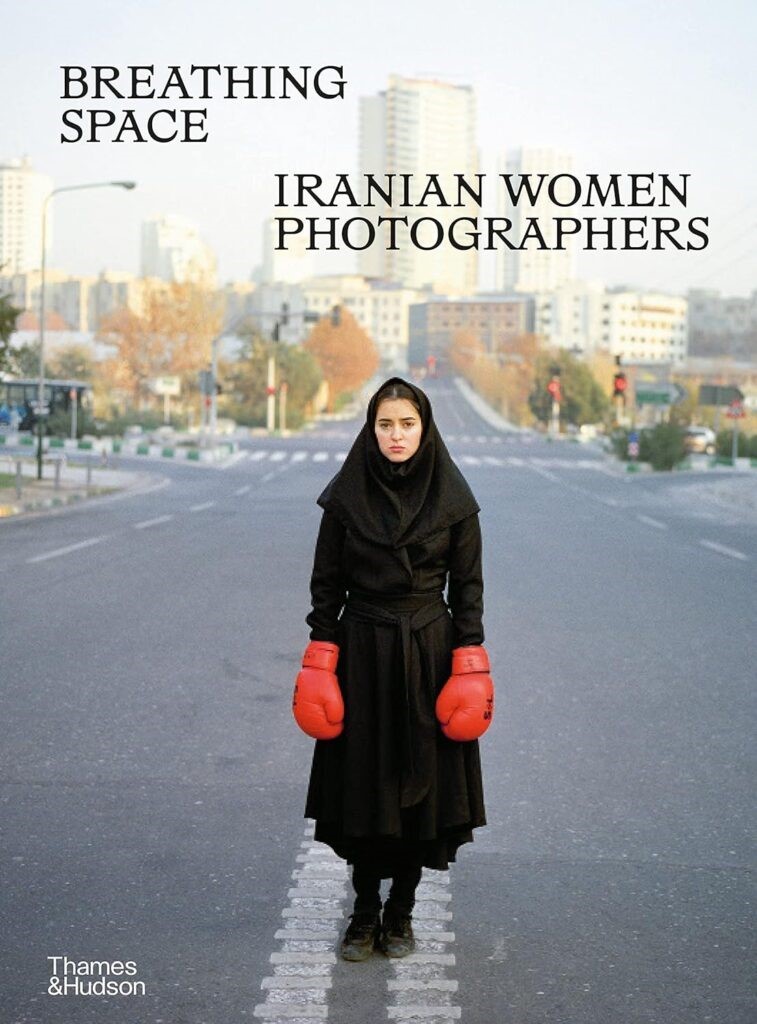

Breathing Space: Iranian Women

Photographers

Breathing Space: Iranian Women

Photographers

by Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh

Amie Ferris-Rotman, Global News

Editor

More

than a year has passed since 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in custody after

being arrested by Iran’s morality police for not wearing a headscarf. The

university student’s death set off the longest-lasting uprising in the Islamic

Republic’s history. Iranian women captured global headlines again when they

joined their Afghan counterparts in launching a campaign to make “gender

apartheid” a law against humanity. In October, the jailed journalist and

activist Narges Mohammadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for fighting the

oppression of Iranian women.

In

“Breathing Space: Iranian Women Photographers,” we are given a visually

stunning perspective of this battle, as told by the country’s women from behind

their lenses. The work spans the life of the regime itself, which is now 44

years old — double Amini’s age at death and considerably older than most of the

protesters in this increasingly youth-populated country. Compiled by the

founder of a photography gallery in Tehran, Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh, the

collection is at times intimate, poetic, and historical. It is always feminist.

The book is also a chilling reminder that their courageous fight is one front,

one extension, of the battle for the rights of women worldwide.

The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the

Land in Between

The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the

Land in Between

by Hisham Matar

Alex Rowell, Online Editor

So

unanimous and extravagant was the acclaim for this book — winner of the 2017

Pulitzer Prize, hailed by everyone from Hilary Mantel to Barack Obama — that I

confidently expected to dislike it when I began reading it this summer. Hours

later, I had missed lunch without noticing, and not even the yells of my

2-year-old son could pull me from its pages, of which I had by then read almost

100 without interruption.

In

astonishingly poised, composed prose, the Booker-nominated Libyan novelist

Hisham Matar tells the true story of his father, Jaballa — a onetime diplomat

for the Moammar Gadhafi regime, who defected to the underground opposition in

the 1970s, and was later abducted in his Cairo home in 1990 by Egyptian secret

police and handed over to Gadhafi as a personal favor from President Hosni

Mubarak, never to be seen by his family again. When Libya’s dictatorship fell

in 2011, Hisham returned to his homeland for the first time in decades, in

search of clues about his father’s fate. That he (spoiler alert) never does

arrive at a definitive conclusion is both disturbing and evocative of a much

wider story in the modern Arab world, where, from Benghazi to Beirut to Baghdad,

the powerful have snatched away so many of their societies’ best and brightest,

not only with total impunity but also a cruel secrecy that denies victims’

loved ones a most basic of courtesies: the knowledge of how their lives ended.

This is a magnificent book, which more than deserves every word of the praise

it has earned.

Eyeliner: A Cultural History

Eyeliner: A Cultural History

by Zahra Hankir

Ola Salem, Managing Editor

Renowned

British-Lebanese writer Zahra Hankir gifted us all another gripping book this

year, this time on the cultural history of eyeliner. As an Egyptian who has

worn eyeliner almost every day for the past two decades, I was left with an

even greater fondness for the makeup tool. Not only did I discover that my

go-to Rimmel eyeliner during college days was the same used by the late singer

Amy Winehouse, but the amount of discoveries the pages drip with meant this was

one of those light and fascinating reads that flowed so smoothly, much like how

every eyeliner wing should.

Looking for Dilmunby Geoffrey Bibby

Looking for Dilmunby Geoffrey Bibby

Lydia Wilson, Culture Editor

One

of the joys of used bookstores is that you find books you would never have

known about through any other route. I stumbled on “Looking for Dilmun” during

Britain’s largest antiquarian book fair, which just happens to be held in my

hometown of York. It was displayed on the stand of a 20th-century Middle East

specialist book dealer and stood out among the tales of oil politics and war.

Published in 1970, it tells of the archaeological explorations of author

Geoffrey Bibby and his team in the 1950s and ‘60s, beginning in Bahrain. With

excavation after excavation of completely unknown sites came inevitable — if

relatively speaking — expertise, which other countries in the Gulf began to

call on. Over the next 12 years, Bibby dug a bewildering amount of sites,

piecing together thousands of years of Gulf history.

The

book describes the process of archaeological discovery and interpretation, and

this emerging history of the region, as well as observing the rapid development

after the discoveries of oil and gas. (Their first visit to Abu Dhabi involved

torches being planted in the ground to guide the planes’ landing … on bare

sand. One tricky moment in Bahrain meant holing up in their camp, hoping that

revolutionaries didn’t come their way.) Told in narrative resembling fiction,

with many wonderful characters along the way, including rulers who have become

very familiar with politics, all three aspects — deep history, modern

development, and the delights and frustrations of archaeology — are gripping.

Technofeudalism: What Killed

Capitalism?

Technofeudalism: What Killed

Capitalism?

by Yanis Varoufakis

Faisal Al Yafai, Executive Editor

Yanis

Varoufakis, former Greek finance minister turned political critic, is always

worth reading, because he sits at the outer edge of daily left-wing politics:

close enough to know the players and occasionally sit at the table, far enough

away not to be sullied by the grubby compromises of power.

His

worldview occupies a particular space at the intersection of big politics

(nation-states, the European Union) and the big companies that interact with

them. In “Technofeudalism,” he directs his anger not at the markets or global

finance — as he has in the past — but at big tech, which has, in his telling,

replaced capitalism. It’s an interesting critique, worth reading because it

signals what a center-left in power — the Democrats in the US, Labour in the

U.K. — might do about big tech’s awesome power.

Kareem Shaheen is Middle East and Newsletters Editor at New Lines magazine.

This article originally appeared in

News Lines magazine.

Disclaimer:

Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Jordan News' point of view.

Read more Opinion and Analysis

Jordan News