New Years’ Day for most of the world starts at midnight in

the dead of winter. That was the date set by Pope Gregory XIII, the 16th

century pontiff who established the modern Western calendar. But across Central

Asia and the

Middle East, it is Mother Nature who determines the beginning of

the year. Kurds, Iranians, and Afghans start their calendars at the vernal

equinox, the astronomical beginning of the year.

اضافة اعلان

Iraq’s

Kurdistan region marks the new year with a

spring-themed party. (It is called Newroz, pronounced “now rose”, in Kurdish.)

Thousands of people leave Erbil, the official regional capital, for Akrê, the

“Newroz capital” in the mountains. Kurdish families dress up in their best

traditional outfits, picnic on the hillsides, dance around bonfires, pick

daffodils, and shoot off fireworks.

Akrê’s festival culminates in a massive torchlit parade into

the mountains on Newroz eve, one that visitors come from around the region to

see. As night falls, the fireworks reach a crescendo. An orange thread winds

its way around the mountains. Smoke fills the air. Some families begin the long

drive back home, while others stay to party all night.

Fireworks and a torchlit parade illuminate the mountains for Newroz (Kurdish New Year) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022.

Fireworks and a torchlit parade illuminate the mountains for Newroz (Kurdish New Year) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022.

The coronavirus pandemic had forced

Kurdish authorities to

cancel past festivities, making 2022 the first “normal” Newroz in two years.

Akrê mayor Mazen Mohammed Said told the Iraqi Kurdish news outlet Rudaw that

around 150,000 people showed up this year. I was one of them, thanks to a

generous invitation from Wladimir van Wilgenburg, a Dutch journalist based in

the region.

Newroz is laden with cultural and political meaning for

Iraqi Kurds. The holiday’s roots stretch back to the earliest civilizations of

the Middle East. Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians celebrated the

first 12 days of

spring as a time of rebirth. (In modern Iran, the new year is

still a 12-day public holiday.) After the long, barren winter, the equinox

meant the return of light, warmth, and fertility.

In the

Babylonian Empire, the chief priest of Babylon would

symbolically re-coronate the king. In the Persian Empire, nobles would gather

in the ceremonial capital of Persepolis with gifts for the emperor.

“By ritually rehearsing cosmic battles that had ordered the

universe at the beginning of time, the ruling aristocracy hoped to make this

powerful surge of sacred energy a reality in their state for another 12

months,” religious scholar Karen Armstrong explains in her book Fields of

Blood.

But for Kurds, the holiday has a more subversive meaning.

According to Kurdish mythology, the celebration of Newroz began when a

blacksmith named Kawe overthrew the tyrannical Snake King, who had been

kidnapping children for human sacrifice. Kawe’s followers lit bonfires in the

hills to announce their victory, making fire and the beginning of spring

symbols of freedom.

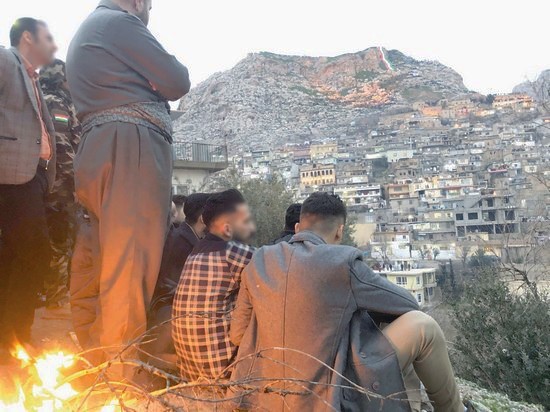

Kurds gather around a bonfire for Newroz (Kurdish New Years) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022. (Photos: Matthew Petti/Jordan News)

Kurds gather around a bonfire for Newroz (Kurdish New Years) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022. (Photos: Matthew Petti/Jordan News)

As Kurds have struggled for an independent state in recent

years, Newroz has become a more nationalistic festival, and the legend of Kawe

has become more pointedly political. Turkey and Syria have repressed Newroz

celebrations, and Saddam Hussein committed his genocidal Halabja massacre a few

days before Newroz in 1988.

Kurdistan achieved autonomy from

Iraq after the Gulf War,

and Akrê became a center of Newroz celebrations soon after. The town — already

famous for its citadel and the shrine of the Sufi saint Abdul Aziz al-Jilani —

began holding Newroz fireworks in the late 1990s. By the 2010s, that became an

organized torch parade.

Over the past few years, its popularity has exploded. The

town of Akrê has a population of 64,000, according to 2014 estimates by Iraq’s

Central Statistical Office. More than double that amount of people showed up

this year for Newroz.

Of course, many visitors means a lot of traffic. The

90-minute drive from Erbil to Akrê can become an hours-long ordeal on Newroz

eve.

Wladimir’s group avoided the traffic by leaving in the

morning. A mix of Kurds and foreigners set out from northern

Erbil a little

after 10am. The roads were still fairly empty and the checkpoints relaxed,

making for a pleasant journey across the green Nineveh Plains and into the

Zagros foothills.

The air was chilly as our group arrived in Akrê a little

before noon. We munched on dolma — one of the traditional Newroz dishes — at

the Xanedan rooftop restaurant. Marchers were already making their way up

Akrê’s peak, which was decorated with a massive Kurdish flag. News crews from

local, Arab and international stations came into the restaurant asking for

interviews.

Kurds parade up a hill with torches for Newroz (Kurdish New Year) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022.

Kurds parade up a hill with torches for Newroz (Kurdish New Year) celebrations in Akrê, Iraqi Kurdistan. March 20, 2022.

We finished our meal and set up a bonfire on a hillside

opposite Akrê’s flag-draped mountain peak. It soon became clear that we were

not leaving. The road was swamped with people and parked cars. A pickup truck

full of friendly Asayish (police officers) had stopped next to us. One group of

vendors set up a stand for tea and snacks.

Outside a convenience store down the road, a different group

of vendors was selling tiny Kurdish flags and an impressive array of fireworks.

Roman candles went for 5,000 Iraqi dinars (JD2.43) each. Teenagers were eagerly

buying them up. An ambulance parked nearby, just as a precaution. A few

fireworks misfired, causing slight panic in the crowd; one of the misfiring

rockets grazed me.

In Iran, both

Persians and Kurds famously celebrate Newroz

by jumping over fire. In Akrê, people gathered around the bonfires instead.

They sat on plastic chairs or danced the govend, a circle dance similar to the

dabkeh.

As the sun drooped closer to the western horizon, the

crackle of fireworks grew louder. It continued as the maghrib azan (dusk call

to prayer) sounded from Jilani’s shrine. Orange lights and smoke began to

spread across the mountains.

The policemen watched the town with binoculars. Kurdish

authorities have been trying to crack down on celebratory gunfire, a dangerous

practice that has caused property damage and accidental deaths. But despite the

police presence, occasional muzzle flashes and tracer rounds burst out from the

mountainside.

Suddenly, a path cleared in the nearby crowd as another

column of marchers with torches appeared behind us. Several of the mountain

peaks around Akrê were now wrapped in strings of orange light.

Booms began to ring out from the citadel. These were the town’s

official fireworks, rather than rockets fired by teenagers. Bright flashes

filled the pitch-black sky. Marchers coming down from the mountain peaks threw

their torches into piles, forming massive bonfires.

As the fireworks died down, some of the crowd stayed to

mingle, while others rushed to their cars, hoping to beat the traffic. But to

no avail — it took hours for the mess of vehicles to untangle itself. People

continued to party in the streets, and one man even launched fireworks out the

window of his taxi.

And then it was over. After getting out of Akrê, the rest of

the drive was smooth, and we arrived back in Erbil a little before 10pm.

The next morning, the city was practically a ghost town as

locals went to picnics or slept in. As my plane took off the next evening, even

the lights of cities and oil wells flickered out and disappeared beneath the

clouds. But an undeniable change had occurred. Spring was here.

Read more Travel